|

Page < 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 >

The history of education in India under the British rule has

yet to be properly written. It should be remembered

that in the pre-British period, India was not an illiterate country. This land

was far more advanced in education than many a Christian country of the West.

Almost every village had its school for the diffusion of not only 3 but 4 R’s

– the last R being religion or the Ramayana. That work has contributed not a

little to the preservation of Hindu culture.

Stress

has not been laid on another fact, which is, that educational institutions were

not established in this country as soon as the East India Company obtained

political supremacy here. It took the Christian merchant “adventurers” just

a century to come to the decision that it was for their benefit to impart

education to the swarthy “heathens” of India. The battle of Plassey was

fought in 1757; and the Wood’s Despatch, commonly called the Educational

Charter of India, is dated 1854. This should show that the system of education

was not introduced in hot haste but after the mature deliberation of nearly a

century. Stress

has not been laid on another fact, which is, that educational institutions were

not established in this country as soon as the East India Company obtained

political supremacy here. It took the Christian merchant “adventurers” just

a century to come to the decision that it was for their benefit to impart

education to the swarthy “heathens” of India. The battle of Plassey was

fought in 1757; and the Wood’s Despatch, commonly called the Educational

Charter of India, is dated 1854. This should show that the system of education

was not introduced in hot haste but after the mature deliberation of nearly a

century.

It should also not be lost sight that the Indians themselves

were the pioneers of introducing Western education in this country. The Hindu

College of Calcutta was established long before Macaulay penned his celebrated

minute or wood sent out his Educational Despatch to India.

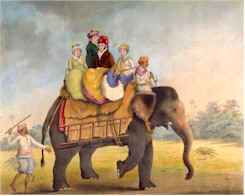

When the East India Company attained political supremacy in

India, they did not bestow any thought on the education of the inhabitants of

their dominions. Gold was their watchword. Everyone of their servants who came

out to India tried to enrich himself as quickly as possible at the expense of

the children of the soil. It was on this account that Edmund Burke described

them as “birds of prey and passage” in India.

According to Herbert Spencer,

“The Anglo-Indians of the last century – “birds of prey and passage, “

as they were styled by Burke – showed themselves only a shade less cruel than

their prototype of Peru and Mexico.”

These residents of Britain after making their fortunes

retired in England, where they were known as “Indian Nabobs.”

The Christian “Indian Nabobs”

looked on the heathens of India in the same light as their co-religionists of

America did on their Negro slaves. Writes a historian: “On the

contrary, the education of Negroes was expressly forbidden. Here, for instance,

are some passages from the Code of Virginia in 1849; “Every assemblage of

Negroes for the purpose of instruction in reading or writing shall be an

unlawful assembly. (Harmsworth: History of the World vol. IV p. 2814).

But as years rolled on, it became patent to some thoughtful

Anglo-Indians, that their dominion in India could not last long unless education

– especially Western – was diffused among the inhabitants of that land. But

this proposition struck terror and dismay into the hearts of the generality of

the people of England.

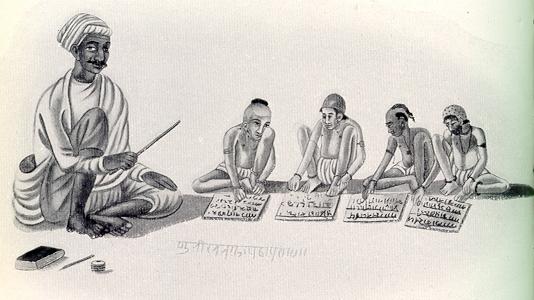

It should be remembered that India

was NOT a country inhabited by savages and barbarians. In the pre-British period,

India possessed educational institutions of a nature which did not exist in the

countries of the West. That even in the beginning of the Nineteenth

century, India, in the matter of education, was in advance of the European

countries is proved by the fact of her teaching those countries a new system of

tuition, to which attention was drawn by the Court of Directors in their letter

to the Governor-General-in-Council in Bengal, dated 3rd June, 1814,

extracts from which have been already given above. Very few in India know that

the system of “mutual tuition”

– which has been practiced by Indian school-masters since time

immemorial – has been borrowed by the Christian countries of the West from

India. The man who first introduced it into Great Britain was a native of

Scotland by the name of Dr. Andrew Bell

(1753-1832). It should be remembered that India

was NOT a country inhabited by savages and barbarians. In the pre-British period,

India possessed educational institutions of a nature which did not exist in the

countries of the West. That even in the beginning of the Nineteenth

century, India, in the matter of education, was in advance of the European

countries is proved by the fact of her teaching those countries a new system of

tuition, to which attention was drawn by the Court of Directors in their letter

to the Governor-General-in-Council in Bengal, dated 3rd June, 1814,

extracts from which have been already given above. Very few in India know that

the system of “mutual tuition”

– which has been practiced by Indian school-masters since time

immemorial – has been borrowed by the Christian countries of the West from

India. The man who first introduced it into Great Britain was a native of

Scotland by the name of Dr. Andrew Bell

(1753-1832).

The village communities of India had not then been destroyed,

and it being the duty of every village communities to foster education, a school

formed a prominent institution in every village of any note. Thus one Mr. A.

D. Campbell, Collector of Bellary, wrote in his Report dated 1823, as

follows:

“The economy with which children are taught to write in the

native schools and the system by which the more advanced scholars are caused to

teach the less advanced, and at the same time to confirm their own knowledge, is

certainly admirable, and well deserved the imitation

it has received in England.”

He then goes on to remark, "of nearly a million souls

not 7000 are now at school." The decimation of the Indian education system

thus created a vacuum that then had to be filled. Into that vacuum, eager and

waiting, went the missionaries, who swiftly set up their own church-sponsored

schools and taught Indian children their own literature and history according to

the gospel of Max Muller. It is by now a well-established fact that education

was a means to Christianize and "domesticate" the native population

and render it loyal to the British empire.

(Extracts from the report of A.D.

Campbell, Esq., the Collector of Bellary, dated Bellary, August 17,

1823, upon the Education of the Natives: p. 503-504 of Report from Select

Committee on the affairs of the East India Company, vol. 1. published 1832).

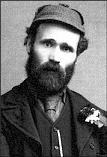

The late Mr. Keir Hardie

(1856-1915) Britain's

first Labor MP, in

his work on India, (p. 5), wrote: The late Mr. Keir Hardie

(1856-1915) Britain's

first Labor MP, in

his work on India, (p. 5), wrote:

“Max Muller, on the strength of official documents and a

missionary report concerning education in Bengal prior to the British

occupation, asserts that there were 80,000

native schools in Bengal, or one for every 4000 of the population. Ludlow,

in his History of British India, says that “in

every Hindoo village which has retained its old form I am assured that the

children generally are able to read, write, and cipher, but where we have swept

away the village system, as in Bengal, there the village school has also

disappeared.”

With the destruction of the village communities and the

impoverishment of the people which are inseparably connected with the British

mode of administration of India, educational institutions which used to flourish

in every village of note became things of the past.

Walter Hamilton, writing in 1828 from official records said:

“It has long been remarked that science and literature are in a progressive

state of decay among the natives of India, the number of learned men being not

only diminished, but the circle of learning,….the principal cause of this

retrograde condition of literature may be traced to the want of that

encouragement which was formerly afforded to it by princes, chieftains and

opulent individuals, under the native governments, now past and gone. (vol. 1.

p. 203).

The British administrators of India

of those days were actuated by political motives in keeping Indians ignorant.

Thus one gallant Major General Sir Lionel Smith, K.C.B., at the enquiry of 1831,

said:

“The effect of education will be to do away with all the

prejudices of sects and religions by which we have hitherto kept the country –

the Mussalmans against Hindus, and so on; the effect of education will be to

expand their minds, and show them their vast power.”

Conversion and Education of Hindus:

The Situation in 1813

In the Charter Act of 1813,

to promote the happiness of the heathens of India, it was proposed that:

“such measures ought to be adopted as may tend to the

introduction among them of useful knowledge, and of religious and moral

improvement; and in furtherance of the above objects, sufficient facilities

ought to be afforded by law to persons desirous of going to and remaining in

India, for the purpose of accomplishing those benevolent designs.”

Before proceeding further, it is necessary to point out the

diplomatic language of the above clause of the Charter Act. It is language

befitting a Machiavelli or a Talleyrand – which does not so much express as

conceal the thought and objects which the framers of the Act had in view. Who

are the persons referred to as “desirous of going to and remaining in India,

for the purpose of accomplishing those benevolent designs?” They

were Christian missionaries.

***

At the time of the East India Company charter of 1813,

education in England was still under the control of the Church. Hence, the

framers of the charter could not think of imparting education to Indians without

ecclesiastical agency. This explains the diplomatic language of the Charter.

It would have been outraging the feelings of Indians to have

informed them of the ecclesiastical Department that they were going to be

saddled with, for the benefit of the Christian natives of England. Hence the

diplomatic language of the Charter Act.

Warren Hastings was asked

by the Lords’ Committee:

“would the introduction of a Church establishment into the

British territories in the East Indies, probably be attended with any

consequences which would be injurious to the stability of the Government of

India?”

Sir Malcolm told the

Lords Committee:

”With the most perfect conviction upon my mind, that, speaking humanly, the

Christian religion has been the greatest blessing that could be bestowed on

mankind….In the present extended state of our Empire, our security for

preserving a power of so extraordinary a nature as that we have established,

rests upon the general division of the great communities under the Government,

and their subdivision into various castes and tribes; while they continue

divided in this manner, no insurrection is likely to shake the stability of our

power. “

Hastings and Malcolm and others,

opposed the introduction of Christian missionaries in India and imparting of

knowledge to its inhabitants from considerations of political expediency. But it

was on grounds of political expediency, too, that these two measures were

advocated.

It was Charles Grant,

described as the Christian Director of the East India Company, who was the first

to press upon the British public the expediency of sending Christian

missionaries to India for the conversion of its heathen inhabitants, and the

imparting them education. We read

in his biography that Grant always kept his eye fixed on the chief object of his

heart – the evangelization of India. In order to succeed in his endeavor, he

did what the Christian missionaries are in the habit of doing to this day, that

is, vilifying, and painting the natives of India in the blackest color possible.

Again he wrote: “By planting our language, our knowledge,

our opinions, and our religion, in our Asiatic territories, we shall put a great

work beyond the reach of contingencies; we shall probably have wedded the

inhabitants of those territories to this country.”

That is quite true. The Christian nations and countries of

the West sent missionaries of their faith to non-Christian nations, not so much

for the spiritual welfare of the latter, as for the worldly good which these

missionaries bring to the Christian nations.

That

Indian patriot, Lala Lajpat Rai, who was

deported out of India without any trial and without knowing the nature of the

charges against him, wrote in a letter from America, which he visited in 1905: That

Indian patriot, Lala Lajpat Rai, who was

deported out of India without any trial and without knowing the nature of the

charges against him, wrote in a letter from America, which he visited in 1905:

“ The other day there was held a conference of missionaries

in which President Copen is said to have

advocated the extension of the mission work for the benefit of the American

trade. He said, in part, we need to develop foreign missions to save our nation

commercially….It is only as we develop missions that we shall have a market in

the Orient which will demand our manufactured articles in sufficient quantities

to match our increased facilities. The Christian man is

our customer. The heathen, has, as a rule, few wants. It is only when

man is changed that there comes this desire for the manifold articles that

belonged to the Christian man and the Christian home. The missionary is

everywhere and always the pioneer of trade..”

Commenting on the above extract, Lala Lajpat Rai very rightly

observed:

“The Indian admirers and friends of Christian missions ought

to note this commercial ideal of the American missionary. The

missionary is not ‘the pioneer of trade’ only but also the pioneer of the

political supremacy of the Boston people of the East. I think the frank

statement of leading Christians ought to open the eyes of all who see no danger

in the work of the Christian Missions in the East.”

If truth be told, it must be

admitted that Christian nations are not anxious to save the souls of the

heathens but wish to enrich themselves, and, therefore, send missionaries to

non-Christian lands. Charles Grant wanted to keep the natives of

India perpetually under the leading strings of his own countrymen. He wrote

that,

“We can foresee no period in which we may not govern our

Asiatic subjects, more happily for them than they can be governed by themselves

or any other power; and doing this we should not expose them to needless danger

from without and from within, by giving the

military power into their hands.”

According to him, neither conversion to Christianity nor

imparting of instruction to the natives was calculated to inspire them with any

desire for liberty. Neither Charles Grant nor the natives of England were

prompted by any motive of philanthropy or altruism to grant these measures to

India. It was sordid considerations of worldly gain which led the people of

England to adopt the above measures under the cloak of philanthropy.

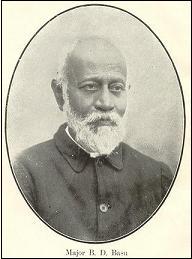

(source:

Education in India Under The Rule of the East India

Company - By Major B. D. Basu 1934 2nd edition. Calcutta).

***

As

the British came to India on a civilizing mission (Nandy, 1983), with the ideology of a tough,

courageous, openly aggressive, and hypermasculine rulers (Nandy, 1987), India's

traditional ways were discredited, disregarded, short-circuited and even

ridiculed (Srinivas, 1999). The

impact of colonialism was deep, causing depreciation and trivilization of

ancient Indian knowledge and qualities, and all excellence "was abolished as effectively as by decree" (Anand,

1961, p.69), resulting

in the denigration of native excellence. To the colonizers, the intellectual potential

of the Indians was a fixed limited quantity, and not a variable. However, narrow

scholasticism and a very limited view of Indian abilities received sanction in

colonial India and thus excellence suffered from a particular stereotype (Gore,

1985).

The

education tradition of the colonial powers still permeates practices in the

post-colonial India and, indeed, the Westernization of the educational system

has been far greater since independence than under British rule. This

has produced a new class that is ever looking towards Europe and America. Even

after 50 years of independence in India, we have neither been able nor seem to

be taking effective steps towards liberating ourselves from the colonial

domination. Though similar concerns have been raised by scholars in various

fields including art and culture, the programs for identification and urturance

of excellence in India are heavily loaded with the classical Western thinking

and conceptualization, discrediting the indigenous notion of excellence.

(source: India's

search for excellence - By Raina,

M.K, Srivastava, Ashok K -

Jan

2000, Vol. 22 Issue 2, p 102, 7p http://www.roeperreview.org/ ).

Is

the March over?

By Mario Cabral E Sa, Goa

Hindustan Today

October, 1997

"When all are baptized, I order all temples of

their

false gods destroyed and idols broken into pieces. I can

give you no idea of the joy I feel seeing this done."

- Saint Francis Xavier (1506-1552)

In 1567 The

captain of Rachol Fort in South Goa bragged to his Portuguese king back home, "For

nights and nights went on the demolishing, demolishing, demolishing of 280 Hindu temples.

Not one remained in the happy lands of our division." Jesuit historian Francisco de

Souza jubilantly praised the feat, "It is incredible-the sentiment that the gentile

were seized of when they saw their respective temple burning." The astonishing but

true fact is that every temple was soon relocated and rebuilt by my countrymen; the

murtis, and in some cases the sacred fire, were heroically rescued and reinstated.

Chandrakant Keni, a leading Goan poet, says that although Goa's Hindus were put to severe

tests as conquerors marched over their lands, they had the resilience to convert

"temporary setbacks into permanent victories."

Goa is located on the southwest coast of India between Karnataka and Maharashtra states.

It remained a Portuguese colony until forcibly taken by India in 1961. The "Christian

presence in Goa-an expression very much in vogue during the evangelistic fury of the

Portuguese rulers and padres (priests), particularly in the 16th and 17th centuries-is

more visible than vital today, 35 years after liberation. For example, Rodale's Guide to

Places of the World describes Goa as "predominantly Catholic," when in reality

Hindus, 66% of the 1.2 million populace, far outnumber Christians of all denominations.

The first

missionaries realized early on that despite backing of the state ("conversions were

made," wrote contemporary Portuguese chroniclers, with "the cross in one hand,

the sword in the other"), it was difficult to wean Goans from their primal Hindu

beliefs and traditions. I will share a traumatic and rancorous twist of this Hindu

stalwartness that involved the splitting up

of my ancestral family. They took a calculated risk: half the family would convert, and

the other would escape to Karnataka where other Goan Hindus had settled and been welcomed

by the Ikkeri king. The half that remained would safeguard the estate and assets of the

migrating half. The calculation was that the Portuguese wouldn't stay in Goa for long-just

trade, make money and go. That didn't happen. By the 1800s it was clear the Portuguese

would remain. By then, too, the converted half of my family was forced to eat beef and

pork and felt they could not return to their primal Hindu faith. They had by then

appropriated the estate and assets of the migrated half, rather than lose it to the

Inquisition, as the law then stipulated properties belonging to the "heathen" be

confiscated.

Noted India cartoonist/illustrator Mario De Miranda confirms his family's fidelity,

"I am a Saraswati Brahmin, originally named Sardessai. My ancestors were forcibly

converted to Christianity around 1600 and renamed Miranda. We still belong to the Shanta

Durga temple and yearly present prasad-oil and a bag of rice-a tradition in my family all

these years."

Early European

travellers, like Venetian epicure

Pietro Della Valle who visited Goa in the 1700s, denounced in their travelogues

"un-Christian" practices in Catholic churches and shrines in Goa. Rather than

create for themselves insurmountable trouble, the padres, particularly the Jesuits,

reluctantly rewrote Christian liturgy. For instance, they enthusiastically adopted the

Hindu tradition of yatra-in the Goan sense of "procession." Neophytes, according

to chroniclers, paraded to their new Catholic shrines, singing as they moved and showering

their paths with leaves and flowers, just as they had done only a while earlier as Hindus.

To this day kumbhas are used for Catholic processions. At one stage, even the Vatican

tersely censured those "gentilic practices" and proliferation of icons in

churches. No where, lamented Della Valle, had he seen as much idolatry as in Goan

churches. But evangelists, many of them foreigners-the most successful was Saint Francis

Xavier-convincingly argued that without ethnic accommodations they were doomed to failure.

Other concessions included retainment of social

structures. In 1623 Pope Gregory gave sanction for converted Brahmins to continue wearing

their sacred thread and caste marks, and Catholics to this day maintain the Hindu caste

system. Till recently, inter- caste marriages among Catholics were frowned upon both by

families and the religious establishment, and though love marriages are increasing,

arranged marriage is still preferred. Only Catholics descending from brahmin families were

admitted to seminaries until the 17th century.

Hindu influence is also evident in Goa's Christian art. Icons of Christ have the angular

and emaciated features of a Himalayan sadhu, and statues of Mary contain the features of

Parvati, Lakshmi or other Hindu deities. Many angels and cherubs sculpted on altars and

pulpits of Christian shrines resemble apsaras and gopikas.

At times, the zeal lead to humorous situations. At village Moira, in north Goa, a Siva

temple was destroyed and replaced by a church dedicated to the Immaculate Conception of

Mary. Apparently, the builder had found the tripartite Sivalinga of the original temple

and not knowing its symbolism but realizing its artistic value, used it as a pedestal for

the holy water basin. And there it was, from 1636 to 1946, when German indologist Gritle V

Mitterwallner noticed it during a monument survey. He decided to move the Sivalinga to the

Museum of the Archaeological Survey of India in Old Goa, and paid for a masonry pedestal

for the basin.

Obsessed with quick results, Portuguese evangelists brainwashed with a singular lack of

concern for substance and almost psychotic emphasis on form. Numbers mattered, not

quality. They force-fed Goan converts beef and pork declaring-incorrectly-that the

neophytes could never return to Hinduism. They also forced converts to change their

lifestyles, but never really thought of teaching the natives basic Christianity. So much

so, in the early 1990s Goa Catholic leaders admitted that fundamentalist Christian sects

like the "Believers" (akin to Liberation theologians), then on the upswing, were

infiltrating the mainstream Catholic community precisely because the community lacked

adequate religious foundation. It was realized that only a few had actually ever read or

studied the Bible. In fact, the Old Testament had never been translated into Konkani, the

mother tongue of Goans and spoken by over 90% of them.

Perhaps this accounts for a current trend, since

Goa's liberation, of Catholics' reverting to Hindu practices, seen in several arenas. Many

offer prasad at Hindu temples like Fatarpa. Fisherfolk celebrate Nariel Purnima to begin

the fishing season and propitiate Samudra Gods with coconut offerings. New babies are

given Hindu names, and some adults are now shedding their Catholic names to adopt Hindus

ones. Some Catholics observe the 12th day samskara after birth and death. Many women now

wear the mangalsutra and forehead bindis, and use mehndi to embellish palms and soles.

Indian dress is more fashionable (kurtas, saris, etc.) and rotis (flatbread) are a

Catholic staple.

Hindus are culturally strong, but understandably influenced by Christianity. Goans of both

communities celebrate together socially at festivals like Divali and Christmas, though

essential religious rituals are attended separately. Hindus do not attend Christian

churches, though quite a few, particularly of lower castes, in a crisis or in gratitude

for favors perceived as granted, propitiate Catholic "miraculous saints."

Influence also occurs educationally. The majority of colleges are Catholic and in them

Hindu students outnumber Catholic students. Unfortunately, Hindus attending these schools

are often subtly weakened in their beliefs.

Having failed to change the Goan psyche, the Portuguese developed a paranoia for

appearance. In the 1700s Captain Alexander Hamilton counted eighty churches in the capital

alone, and 30,000 priests. "Each church's bells," he wrote, "continually

rang with a peculiar power to drive away all evil spirits except poverty in the laity and

pride in the clergy." Today, there are 6-700 priests, many churches are closed except

for festivals, and old chapels are in disuse.

In contrast, Hindu temples are flourishing. The

Bhahujan Samaj, disadvantaged until 1962, is socially and politically powerful. They have

established a non-brahmin prelate at the Haturli Mutt (monastery), and the temple under

construction there may be worth Rs. ten million ("$290,000) by completion. Other

thriving mutts are Partagal and Kavalem. Modern Hindus feel duty-bound to restore their

heritage, exemplified by Damodar Narcinva Naik who owns Goa's largest car dealership.

Besides starting a movement to popularize Sanskrit, he had the Veling temple and Partagal

Mutt rebuilt according to old Hindu architectural norms. And Dattaraj Salgaonkar, a young

entrepreneur who recently helped restore the Margao Mutt in South Goa says, "Ibis

mutt was demolished by invaders in order to exterminate the Saraswat community and

eliminate its influence over many followers." Curiously, when Goans part company with

friends or relatives we say "Yetam," which means "I'll come back," not

as elsewhere, "Vetam I'm going."

It's our way of expressing hope and optimism.

How the British Looted India

http://www.ummah.net/history/naval_crusades/india2.htm

- (please note: this page has been removed)

In 1787 a former army officer wrote: In former times

the Bengal countries were the granary of nations, and the repository of commerce, wealth

and manufacture in the East...But such has been the restless energy of misgovernment, that

within 20 years many parts of those countries have been reduced to desert. The fields are

no longer cultivated, extensive tracks are

already overgrown with thickets, the husbandman is plundered, the manufacturer

(handicraftsman) oppressed, famine has been repeatedly endured and depopulation ensured. In 1787 a former army officer wrote: In former times

the Bengal countries were the granary of nations, and the repository of commerce, wealth

and manufacture in the East...But such has been the restless energy of misgovernment, that

within 20 years many parts of those countries have been reduced to desert. The fields are

no longer cultivated, extensive tracks are

already overgrown with thickets, the husbandman is plundered, the manufacturer

(handicraftsman) oppressed, famine has been repeatedly endured and depopulation ensured.

As India became poor and hungry, Britain became richer. Colossal

fortunes were made. Robert Clive arrived in India penniless - activities of Company

investigated by House of Commons. The Hindi word loot was introduced into

English language because of the plunder of India. Colossal fortunes helped fund

Britain's Industrial Revolution e.g.:

1757 - Battle of Plassey

1764 - Hargreaves spinning jenny

1769 - Arkwright's water frame

1779 - Crompton mule (whatever that is)

1785 - Watt's steam engine

When British first reached India they did not find a backwater

country. A report on Indian Industrial Commission published in 1919 said that the

industrial development of India was at any rate not inferior to that of the most advanced

European nations. India was not only a great agricultural country but also a great

manufacturing country. It had prosperous textile

industry, whose cotton, silk, and woollen products were marketed in Europe and Asia. It

had remarkable and remarkably ancient, skills in iron-working. It had its own shipbuilding

industry in Calcutta, Daman, Surat, Bombay and

Pegu. In 1802 skilled Indian workers were building British warships at Bombay. According

to a historian of Indian shipping the teak wood vessels of

Bombay were greatly superior to the oaken walls of Old England. Benares was famous all

over India for its brass, copper and bell-metal wares. Other important industries included

the enamelled jewellery and stone carving of

Rajputana towns as well as filigree work in gold and silver, ivory, glass, tannery,

perfumery and papermaking.

All this altered under the British leading to the de-industrialisation of India - its

forcible transformation from a country of combined agriculture and manufacture into an

agricultural colony of British capitalism. British annihilated Indian textile industry

because a competitor existed and it had to be destroyed. Shipbuilding industry aroused the

jealousy of British firms and its progress and development were restricted by legislation.

India's metalwork, glass and paper industries were likewise throttled when British

government in India was obliged to use only British-made paper.

All this altered under the British leading to the de-industrialisation of India - its

forcible transformation from a country of combined agriculture and manufacture into an

agricultural colony of British capitalism. British annihilated Indian textile industry

because a competitor existed and it had to be destroyed. Shipbuilding industry aroused the

jealousy of British firms and its progress and development were restricted by legislation.

India's metalwork, glass and paper industries were likewise throttled when British

government in India was obliged to use only British-made paper.

The vacuum created by the contrived ruin of the Indian handicraft

industries, a process virtually completed by 1880, was filled with British manufactured

goods. Britain's industrial revolution, with its explosive increase in productivity made

it essential for British capitalists to find new markets. India turned from exporter of

textile or importer. British goods had to have virtually free entry while entry into

Britain of India goods was met with prohibitive tariffs. Direct trade between India and

the

rest of the world had to be curtailed. Horace Hayman Wilson in 1845 in The History of

British India from 1805 to 1835 said the foreign manufacturer employed the arm of

political injustice to keep down and ultimately strangle a competitor with whom he could

not have contended on equal terms.

While there was prosperity for British cotton industry there was ruin for millions of

Indian craftsmen and artisans. India's manufacturing towns were blighted e.g. Decca once

known as the Manchester of India, and Murshidabad-Bengal's old capital which was once

described in 1757 as extensive, populous and rich as London. Millions of spinners, and

weavers were forced to seek a precarious living in the countryside, as were many tanners,

smelters and smiths.

India was made subservient to the Empire and vast

wealth was sucked out of Economic exploitation was the root cause of the Indian people's

poverty and hunger.

Under Imperial rule the ordinary people of India grew steadily poorer. Economic historian

Romesh Dutt said half of India's annual net revenues of £44m flowed out of India. The

number of famines soared from seven in the first half of 19th Century to 24 in second

half. According to official figures, 28,825,000 Indians starved to death between 1854 and

1901. The

terrible famine of 1899-1900 which affected 474,000 square miles with a population almost

60 million was attributed to a process of bleeding the peasant, who were forced into the

clutches of the money-lenders whom British regarded as their mainstay for the payment of

revenue. The Bengal famine of 1943, which claimed 1.5million victims were accentuated by

the authority's carelessness and utter lack of foresight.

Rich though its soil was, India's people were hungry and miserably poor. This grinding

poverty struck all visitors - like a blow in the face as described by India League

Delegation 1932. In their report Condition of India 1934 they had been appalled at the

poverty of the Indian village. It is the home of stark want...the results of uneconomic

agriculture, peasant

indebtedness, excessive taxation and rack-renting, absence of social services and the

general discontent impressed us everywhere..In the villages there were no health or

sanitary services, there were no road, no drainage or lighting, and no proper water supply

beyond the village well. Men, women and children work in the fields, farms and

cowsheds...All alike work on

meagre food and comfort and toil long hours for inadequate returns.

Jawaharlal

Nehru wrote that those parts of India which had been longest under British rule were the

poorest: Bengal once so rich and flourishing after 187 years of British rule is a miserable

mass of poverty-stricken, starving and dying people. Jawaharlal

Nehru wrote that those parts of India which had been longest under British rule were the

poorest: Bengal once so rich and flourishing after 187 years of British rule is a miserable

mass of poverty-stricken, starving and dying people.

India was sometimes called the 'milch cow of the Empire', and indeed at times it seemed to

be so regarded by politicians and bureaucrats in London.

Educated Indians were embittered when India was made to pay the entire cost of the India

Office building in Whitehall. They were further outraged when in 1867 it was made to pay

the full costs of entertaining two thousand five hundred guests at a lavish ball honouring

the Sultan of Turkey.

In India, the hunger and poverty experienced by the majority of the population during the

colonial period and immediately after independence were the logical consequences of two

centuries of British occupation, during which the Indian cotton industry was destroyed,

most peasants were put into serfdom (after the British modified the agrarian structures

and the tax

system to the benefit of the Zamindars - feudal landlords) and cash crops (indigo, tea,

jute) gradually replaced traditional food crops. Britain's profits throughout the 19th

century cannot be measured without taking into account the 28 million Indians who died of

starvation between 1814 and 1901.

"Austenizing"

of British Atrocities in India

(excerpts of article)

By Gideon Polya

http://www.sulekha.com/articledesc.asp?cid=87310

While we are well aware of the selectivity of historians and of the adage

"history is written by the victors," we also recognize the truism that

"history ignored yields history repeated." Thus with the world already

experiencing appalling discrepancies between geopolitically available food and

population demand, the deletion of massive man-made famines of British India

from history and from general public perception is not merely unethical -- such

white-washing also represents a major threat to humanity. Deletion of major

man-made catastrophes from history increases the probability that the same

underlying, but unaddressed, causes will yield repetition of such disasters.

I have recently published a book --

"Jane

Austen and the Black Hole of British History. Colonial Rapacity, Holocaust

Denial and the Crisis in Biological Sustainability" -- that deals with

the two century holocaust of man-made famine in British India and its effective

deletion from history. It deals with this "forgotten holocaust" that

commenced with the Bengal Famine of 1769-1770 (10 million victims) and concluded

with the World War II man-made Bengal Famine (4 million victims) and took tens

of millions of lives in between. The lying by omission of two centuries of

English-speaking historians continues today in the supposedly "open

societies" of the global Anglo culture. This

sustained, continuing lying by omission in the sophisticated but cowardly and

selectively unobservant culture of the Anglo world has ensured that very few

educated people (including Indians) are aware of these massive past realities.

In contrast, nearly all are aware of the substantially fictional "Black

Hole of Calcutta" of 1756 that demonized Indians and indeed became part of

the English language.

Repetition of immense crimes against humanity such as

the World War II Holocaust is made much less likely when the responsible society

acknowledges the crime, apologizes, makes amends and accepts the injunction:

"Never again." However, when it comes to the horrendous succession of

massive, man-made famines in British India, no apology nor amends have been made

and it is indeed generally accepted that such horrors will be repeated on an

unimaginably greater scale in the coming century.

(For the rest of article please go to the above

site)

White

Man’s Burden: Indian Holocaust

By A. P. Kamath

2/18/2001

www.rediff.com

In trying to buttress his thesis about the death of 32-61

million people from famines in India, China and Brazil in the 19th

century, author and political activist Mike Davis poses the question: “How

do we weigh smug claims about the life-saving benefits of steam transportation

and modern grain markets when so many millions, especially in British India,

died along railroad tracks or on the steps of grain depots?”

Davis, a winner of the $315,000 Mac Arthur Foundation grant

given annually to “exceptionally creative individuals,” answers his question

in the book Late Victorian Holocausts (Published by Verso, $27). Its

second title: El Nino Famines and the Making of the Third World.

He argues that while the El Nino weather phenomenon

contributed to the droughts in the last third of the 19th century,

the death of millions was due to the arrogance and callous policies of

imperialist powers. He slams the official British explanation that millions were

killed by extreme weather.

The killer, Davis argues, was

imperialism.

If the governments had made serious efforts to use

transportation system to benefit the poor, he says, there would not have been a

famine holocaust. He notes that the British

rulers launched public work programs to fight famine in India but the

workers, already emaciated, got such poor food that their health deteriorated

further.

Davis asserts that what is known as

the Third World today was born in the late 19th century; the seeds of

underdevelopment were sown during the height of imperialism. The price for

capitalist modernization and the industrial revolution was paid in the blood and

toil of farmers’ lives.

Mike Davis, 52, is one of the most controversial political

writers in America. The son of a meat cutter, Davis dropped out of high school

to follow his father’s profession.

Among his widely discussed books is City of Quartz, a

bitter indictment of the whites who run Los Angeles—and the economic disparity

and racial politics. His critics have slammed him for exaggerating racial and

political issues confronting the city. But his backers see him as a perceptive

critic and a conscience keeper who does not hesitate to speak out his mind.

Winning the Mac Arthur award helped Davis to continue the

research that resulted in the present book. Though Late Victorian

Holocausts was published by a small avowedly leftist press in New York, it

is getting plenty of attention in mainstream publications.

Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen, who gave it a page-long review in

The New York Times Book Review, found the book “gripping” and

“highly informative.”

Where

the missionaries come in - Now,

Vasco da Gama's misdeeds

By M.V. Kamath

http://www.expressindia.com/columnists/kamath4.htm

(link for this article is broken)

Empires

of the Monsoon; The History of the Indian Ocean and its invaders; by Richard Hall;

Harper Collins; pages 575; 9.99 pounds

Until Vasco da Gama discovered the sea route to the East in 1497-1499, the

"West knew little about India let alone the countries further east. It is

not that there was no awareness of India in the West, meaning thereby mainly

Europe. Marco Polo had come visiting India and there certainly was a lively

trade between north India and central Asia. Indian silk, among other

commodities, was justly famous. So were Indian spices. It

was India's misfortune that it should have been 'discovered' by a Portuguese

sailor with criminal intentions.

Issue

of suzerainty

Portugal

and Spain towards the end of the 15th Century were at loggerheads as to who

should claim suzerainty and where. The pope was invited to give a ruling.

According to the Treaty of Tordesillas (signed in June 1494) it was agreed that

everything beyond the meridian of longitude passing 370 leagues west of Cape

Verde Islands was to be exploited by Spain. All the world to the east of the

'Pope's Line' went to Portugal; this embraced Africa and the entire India Ocean.

To say that the Pope of the Catholic Church is not responsible for the

atrocities committed by the Portuguese is to fly in the face of facts. And the

atrocities committed by Vasco da Gama and his men lives in infamy. The story is

one of brutality, betrayal and colonial ambition.

Empires

of the Monsoon is a panoramic study of the history of the Indian Ocean and the

countries on the ocean's periphery. The monsoon determined ship movements -

hence the reference to it in the title of the book. As European invaders,

beginning with the Portuguese and were later to include the Dutch, the British

and the French, began their terrorist tactics, all the countries on the Indian

Ocean Rim began to feel the brutalities of the Europeans. Hall describes them in

great detail. The Europeans traded not just in spices; they were very active in

the slave trade. The Portuguese captured blacks from East Africa and brought

them to Goa. The British literally bought these blacks to be used as soldiers in

Sri Lanka.

The

first to visit India of course was Vasco da Gama. He came with twenty five ships

under his command, of which ten of them contained "much beautiful

artillery, with plenty of munitions and weapons! During his visit to Calicut he

found twenty trading ships in the harbour. Vasco da Gama plundered them and the

800 odd crew were taken prisoners''.

Notes

Hall: With Calicut at his mercy ... da Gama told his men to parade the prisoners

then hack off their hands, ears and noses. As the work progressed all the

amputated pieces were piled in a small boat. The brahmin who had been sent out

by the Zamorin as an emissary was put into the boat amid its new gruesome cargo.

He had also been mutilated in the ordained manner". The historian Gaspar

Correa is quoted by Hall as to what the da Gama did next, thus: "When all

the Indians had thus been executed (sic), he ordered them to strike upon their

teeth with staves and they knocked them down their throats; as they were put on

board, heaped on top of each other, mixed up with the blood which streamed from

them; and he ordered mats and dry leaves to be spread over them and sails to be

set for the shore and the vessels set on fire... and the small, vessel with the

friar (brahmin) with all the hands and ears, was also sent ashore, without being

fired".

Nazi

brutality looks like picnic here

Hall

gives a vivid description of what Vasco da Gama did next which is too gory even

to contemplate. When the Zamorin sent another brahmin to Vasco to

plead for peace, "he had his lips cut off and his ears cut off". The

ears of a dog were sewn on him instead and the brahmin was sent back to Zamorin

in that state. The Brahmin -- no doubt a Namboodiri had brought with him three

young boys, two of them his sons and the other a nephew. They were hanged from

the yardarm and their bodies sent ashore.

Then

there is the story of Alfonso Albuquerque who took his fleet to Goa which had

just been vacated by Adil Shah's armed forces which had been sent elsewhere to

fight. Albuquerque found Goa at his mercy. Hall writes that at this point

Albuquerque "showed all the fondness for atrocities which a lifetime of

fighting in Morocco had taught him". He wrote to the king back in Lisbon as

follows: "Then I burnt the city and put everyone to sword and for four days

your men shed blood continuously. No matter where we found them, we did not

spare the life of a single Muslim; we filled the mosque with them and set them

on fire...We found that 6,000 Muslim souls male and female, were found dead and

many of their foot-soldiers had died. It was a very great deed, Sire". Yes,

it was a great deed indeed. Hall suggests that it may well be that Albuqeerque

was exaggerating his foul deeds to get approval of his monarch, but adds that

"killing certainly came easily to him".

Albuqueque

wanted to turn Goa into a Christian city. He had brought along with him

Portuguese convicts as his soldiers and now he proceeded to force Goan women,

both Hindu and Muslim, to marry these scoundrels. Hall writes with considerable

understatement. "The true feelings of the women chosen for this historic

innovation are not recorded. Albuquerque was particular about those selected,

they had to be good-looking and of white-color. He rejected our of hand, any

potential brides from south India as they were darker".

What

the Portuguese did elsewhere in the Indian Ocean Rim countries followed on these

lines except that the Africans did not have an advanced culture and could thus

be captured and sold as slaves. The one thing that linked India with East Africa

was the monsoon which the Portuguese navigators relied upon to cross the ocean.

If in India the people were unceremoniously killed, the Africans frequently under

Arab (and therefore Muslims) leaders fared no better. How the Portuguese

conquered East Africa to the accompaniment of much suffering of the African

people has to be read to be believed.

Hall

recounts the story of exploration and exploitation with an eye for the exotic

and a penchant for turth. In the end one wishes Vasco da Gama had stayed at home

instead of "discovering India". For that

discovery India had to pay a grievous price. With an India now

resurgent, it should be its specific task to bring to the Ocean Rim countries a

gentler, happier message in contrast to Vasco da Gama's message of wanton

cruelty. India must prove to be their balm and comfort.

Invaders

Aimed to Dismantle Indian Culture (excerpts)

By Jim Martin

http://www.stephen-knapp.com/speaking_out_against_prejudice.htm

" There are many parts of the

world who need humanitarian work, and to do that is fine. However, as a

Christian myself, I know and have heard time and time again this ploy as a

standard tactic to justify why Christians need to go to India and "Deliver

the good news about Jesus" while bringing different kinds of humanitarian

help. I have heard this from local churches as well as numerous television

evangelical preachers as well, such as Jerry Falwell and others, and then watch

them count their success in how many converts they have made. So this is nothing

new. And after a while you begin to see through it. To me this seems completely

unfair to make such an assumption that illiteracy and poverty are caused by

Hinduism, as if Rev. David knows all about the history

of India and why it has lost so much of its glory and power, and the immense

damage the "Christian British" did to India, and its attempt to

dismantle whatever there was of Hinduism and its Vedic literature.

Also, how they purposely controlled food production and distribution of

commodities in order to turn people to Christianity. How they purposely tried to

control and change the Vedic texts to reduce the high standards of living,

morality, and its understanding of God so that people would more easily be

converted to Christianity, along with so many other things they did."

(For the

rest of article please go to the above site). Refer to QuickTime trailer and

Part One of the film The

God Awful Truth.

Did

You Know? Did

You Know?

India - The Holy

Land

For the Hindus, India is a Holy

Land. The actual soil of India is thought by many simple rural Hindus to be the

residence of the divinity and, in villages across India, is worshipped and

understood to be literally the body of the Goddess, while the features of the

Indian landscape - the mountains and forests, the caves and outcrops of rock,

the mighty rivers - are all understood to be her physical features. She is

Bharat Mata, Mother India, and in her main temple in Varanasi the Goddess is

worshipped not in the form of an idol but manifested in a brightly colored map

of India. Her landscape is not dead but alive, dense with sacred significance.

There is a Hindu myth that seeks to

explain this innate holiness. According to legend, Raja Daksha, the

father-in-law of Lord Shiva, failed to invite his son-in-law to an important

event. Overcome by shame, the Daksha's daughter, Sati, jumped into a fire and

killed herself. Shiva, inconsolable, traversed India in a furious, grief stricken

dance, carrying her body. The gods became anxious that Shiva's anguish would

destroy the universe, so they dispersed her body bit by bit, across the plains

and forests of India. Wherever fragments of her body landed, there was

established a tirtha, often a shrine to the Goddess, and in time many of these

tirthas became major pilgrimage centers. There is a Hindu myth that seeks to

explain this innate holiness. According to legend, Raja Daksha, the

father-in-law of Lord Shiva, failed to invite his son-in-law to an important

event. Overcome by shame, the Daksha's daughter, Sati, jumped into a fire and

killed herself. Shiva, inconsolable, traversed India in a furious, grief stricken

dance, carrying her body. The gods became anxious that Shiva's anguish would

destroy the universe, so they dispersed her body bit by bit, across the plains

and forests of India. Wherever fragments of her body landed, there was

established a tirtha, often a shrine to the Goddess, and in time many of these

tirthas became major pilgrimage centers.

The legend encapsulates a picture of

India as a mythologically charged landscape whose holy pilgrimage sites are

widely distributed as the body of Sati itself. The idea

of India's sacredness is therefore not some Western concept grafted onto the

subcontinent in a fit of mystical Orientalism: it is an idea central to India's

conception of self. Indeed the idea of India as a sacred landscape

predates classical Hinduism, and most importantly, is an idea that was in turn

passed onto most of the other religions that came to flourish in the Indian

soil.

(source: Sacred

India - By William Dalrymple

- Lonely Planet Books p. vi-vii).

Page < 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 >

|