|

Page < 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 >

The

Great Farce -

The benign British?

The Colonial Legacy - Myths

and Popular Beliefs -

Fashionable theories of benign

Imperial rule ?

"They

emphasize the improvements in administration, construction of railroad,

universities, abolition of ‘Sati’ and ‘Thugis’ from India and ultimate

peaceful transfer of power to Gandhi-Nehru. According to British

history, there was no freedom movement in

India, no man made famines, no transfer of huge resources from

India

to

Britain, no destruction of Indian industries and agriculture by the British rule, but

only a very benign and benevolent British rule in India."

-

writes Dr. Dipak Basu of Nagasaki

University in Japan

***

The Colonial Legacy - Myths of The British Raj

1. Railways

Romancing the Raj?

Oozing with the milk of human kindness, aren’t we?

Modern Indians

carry this rather ignorant impression that Indians railways was a departing gift

by the British to independent India.

This impression is aided and abetted by Western media

too. Recently,

Robert

Kaplan writing in

The Atlantic

gushed how the “British, by contrast,

brought tangible development, ports and railways, that created the basis for a

modern state” of India.

The end of extraction

Dharmpal

is a noted Gandhian and historian of

Indian science. He is well known for his "rediscovery" of Indian

science. His work has often been path breaking and instilled a whole generation

of Indians with a new-found faith in the country's indigenous scientific

traditions and cultures. Dharmpal

is a noted Gandhian and historian of

Indian science. He is well known for his "rediscovery" of Indian

science. His work has often been path breaking and instilled a whole generation

of Indians with a new-found faith in the country's indigenous scientific

traditions and cultures.

He has recently said:

"The

great myth of British railways and administration misses the point of the kind

of exploitative institutions and ruthless efficiency which culminated in

large-scale famines during and preceding the Second World War, killing millions. "

(source:

Indic

Science - Interview with Dharmpal - timesofindia - January 3

2004).

Sardar

Kavalam Madhava Panikkar (1895-1963)

Indian scholar, journalist, historian from Kerala, administrator, diplomat,

Minister in Patiala Bikaner and Ambassador to China, Egypt and France. Author of

several books, including Asia

and Western Dominance,

India Through

the ages and India

and the Indian Ocean.

Panikkar

wrote: Panikkar

wrote:

"The

19th century witnessed the apogee of capitalism in

Europe. That this was in a large measure due to

Europe

’s exploitation of Asian resources is now accepted by historians.

"It

is the riches of Asian trade flowing to Europe that enabled the great industrial

revolution to take place in England. In the 18th century,

conquest was for the purpose of trade. In the

area you conquered, you excluded other nations, bought at the cheapest price,

organized production by forced labor to suit your requirements, and transferred

the profits to mother country. In the 19th century conquest was not

for trade but investment. Tea plantations and railway

construction became major interests in

Britain

’s connection with India. Vast sums were invested in India

for building railways.

"

As

J

A

(John Atkins) Hobson (1858 - 1940) the

historian of Imperialism, (1902) observes: As

J

A

(John Atkins) Hobson (1858 - 1940) the

historian of Imperialism, (1902) observes:

“The

exploitation of other portion of the world, through military plunder, unequal

trade and forced labor, has been the one great indispensable condition in the

growth of European capitalism.”

(source: Asia

and Western Dominance

- By K M Panikkar p. 316).

When the British decided to

lay a network of rail line in India they gave an impression that it was being

done to improve communication and economic well being of India. But some

enlightened Indians recognized it as an investment in Empire.

The

rail line was not built for the benefit of the natives. It was built with sheer

selfish interest to lay down the foundation for colonialism and promotion of the

British supreme and economic expansionism. At that time, no British mind could

have dared imagine that one day the railway line would be lost only to benefit

the natives.

It is easy to see why British

industry felt very kindly towards the building of railways in India. Railways

were needed by British industry in order that Indian seaports and the interior

districts of the country be interconnected, so that manufactured goods might be

distributed throughout India and the raw products be collected for export to

England.

The

introduction of Railways for example, as everyone knew, was for the twin purpose

of taking away all the agricultural raw materials for

their industrial needs and, for the dumping of the British manufacturers in the

hinterland markets.

Indian

Railways initially was never meant for the sake of Indians and their interests. Similarly

the way Indian agriculture was made to go in the commercial way under the

colonial rule, was to benefit the British Industry by feeding their hungry mills

at the cost of Indian people and peasants.

The

severity of the frequent famines is another scourge of the same place. But to

say that on account of the British rule, there was transport revolution, there

was the linking of the village market to that of the outside markets, that

foreign trade got accelerated, foreign capital multiplied, capital oriented

industries proliferated — is to overlook the fact that all these were

peripheral and unintended to the natives while the major drawback was the huge

drain of wealth that all these economic innovations have brought in their trial.

What answer the history teacher could provide if a

student in the classroom asks for justification for our struggle for

independence if the British rule was so positive.

(source: Distortions

in History - By K S S Seshan - The Hindu November 26, 02).

The infrasructure that the British

created (roads, ports, cities, railway transportation and power grids) were

designed exclusively for the removal of rich resources in as quick and efficient

manner as possible.

Rev. Jabez T. Sunderland author

of India

in Bondage: Her Right to Freedom writes:

"The impression is widespread in America

that British rule in India has been a great and almost unqualified good. The

British themselves never tire of "pointing with pride" to what they

claim to have done and to be doing for the benefit of the Indian people. What

knowledge we have in America regarding the matter, comes almost wholly from

British source, and hence the majority of us do not suspect that there is

another side to the story."

There

have been persistent attempts of Western scholars to argue that "India was

not a country but a congeries of smaller states, and the Indians were not a

nation but a conglomeration of peoples of diverse creeds and sects. Anybody

familiar with the relevant situation will know that this attitude still forms

the major undercurrent of Western scholarship on India. (refer to article: Hindu

Nationalism Clouds the Face of India

- H. D. S. Greenway. Even today the

same attitude is alive and well, Mr. Greenway says in his article:

"Secularists realize that a united India was a product of the British

Empire. Before the British, Indians owed their allegiances to family, clan,

religion, or princely state. We are constantly told that it was the British who established a centralized

administration, a common educational system, and countrywide transportation that

gave the subcontinent a sense of belonging to one country). There

have been persistent attempts of Western scholars to argue that "India was

not a country but a congeries of smaller states, and the Indians were not a

nation but a conglomeration of peoples of diverse creeds and sects. Anybody

familiar with the relevant situation will know that this attitude still forms

the major undercurrent of Western scholarship on India. (refer to article: Hindu

Nationalism Clouds the Face of India

- H. D. S. Greenway. Even today the

same attitude is alive and well, Mr. Greenway says in his article:

"Secularists realize that a united India was a product of the British

Empire. Before the British, Indians owed their allegiances to family, clan,

religion, or princely state. We are constantly told that it was the British who established a centralized

administration, a common educational system, and countrywide transportation that

gave the subcontinent a sense of belonging to one country).

1.

Regarding

countrywide transportation: Railways

American Historian

Will Durant has written in his book - A Case

For India:

"It might have been supposed

that the building of 30,000 miles of railways would have brought a measure of

prosperity to India. But these railways were built not

for India but for England; not for the benefit of the Hindu, but for the purpose

of the British army and British Trade. If this seems doubtful, observe their operation. Their greatest revenues

come, not as in America, from the transport of goods (for the British trader

controls the rates), but from the third-class passengers – the Hindus; but

these passengers are herded into almost barren coaches like animals bound for

the slaughter, twenty or more in one compartment. The railroads are entirely in

European hands, and the Government refuse to appoint even one Hindu to the

Railway Board. The railways lose money year after year, and are helped by the

Government out of the revenues of the people. All the loses are borne by the

people, all the gains are gathered by the trader. So

much for the railways.

Amitav

Ghosh author

of several books, The Circle of Reason (1986), won France's top literary award,

Prix Medici Estranger, and The

Glass Palace also

makes fun of the claim that the British gave India the railways.

"Thailand has

railways and the British never colonized the country," he says.

"In 1885, when the British invaded Burma, the Burmese king was already

building railways and telegraphs. These are things Indians could have done

themselves."

(source: Travelling

through time - interview with Amitav Ghosh).

China and Japan acquired railways without British

colonial rule. Same holds for other Western technology.

The Railways were a win-win situation for Britain

-- Indians took the risk and the British got trains that brought cheap cotton to

the ports to be exported to the mills of Manchester and then distributed the

cloth they manufactured to outlets throughout India. Historians have said the railways were the

mightiest symbol of the Raj, and grand stations like Bombay's Victoria terminus,

a Saracenic-Gothic cathedral of the railway age, and Calcutta's Howrah, cited as

the largest station in Asia, were built to impress

Indians with the might of their rulers.

Mahatma

Gandhi blamed them for carrying "the pest of westernization" around

India.

(source: India's

railways - By Mark Tully).

Note: The

Konkan Railway, the first major railway project in India since Independence, has

been a major success despite the difficult terrain and the logistics nightmares.

As for the story about the Konkan Railway, it is an inspiration. In the face of

obstacles, including extremely difficult terrain (many tunnels, bridges, etc) as

well as the task of raising large amounts of money through a public bond issue,

the railway was constructed on schedule and within budget.

It used to be said that Indians could never match the feats of the British

engineers who built much of India's network; isn't it amazing that E.

Sreedharan, the man who ran this Herculean effort,

is a virtual unknown?

(source:

Historicide:

Censoring the past... and the present).

Commerce on the sea is monopolized by the British

even more than transport on land. The Hindus are not permitted to organize a

merchant marine of their own. All Indian goods must be carried in British

bottoms, an additional strain on the starving nation’s purse, and the building

of ships, which once gave employment to thousands of Hindus is prohibited.

Dadabhai Naoroji

has commented on the building railways in India by the British:

"The misfortune of India is that she does

not derive the benefits of the railways, as every other country does."

(source: Poverty

and Un-British Rule in India - By Dadabhai Naoroji

- p. 103).

***

2. Education:

The

English rulers have boasted that they have introduced education in India but

this boast is pure moonshine.

Literacy

in British India in 1911 was only 6%, in 1931 it was 8%, and by 1947 it had

crawled to 11%! In higher education in 1935, only 4 in 10,000 were enrolled in

universities or higher educational institutes. In

a nation of then over 350 million people only 16,000 books (no circulation

figures) were published in that year (i.e. 1 per 20,000).

Lord Macaulay who created the modern Indian education system, explicitly stated

that he wanted Indians to turn against their own history and tradition and take

pride in being loyal subjects of their British masters. In effect, what he

envisaged was a form of conversion— almost like religious conversion. It was

entirely natural that Christian missionaries should have jumped at the

opportunity of converting the people of India in the guise of educating the

natives. So education was a principal tool of

missionary activity also. This produced a breed of ‘secular

converts’ who are proving to be as fanatical as any religious fundamentalist.

We call them secularists.

Macaulay,

and British authorities in general, did not stop at this. They recognized that a

conquered people are not fully defeated unless their history is destroyed.

(source: Tortured

souls create twisted history - N S Rajaram - bharatvani.org

and The

Colonial Legacy - Myths and Popular Beliefs).

"Every village had its schoolmaster, supported out of the public funds; in Bengal

alone, before the coming of the British, there were some 80,000 native schools -

one to every four hundred population. Instruction was given to him in the

"Five Shastras" or sciences: grammar, arts and crafts, medicine, logic

and philosophy. Finally the child was sent out into the world with the wise

admonition that education came only one-fourth from the teacher, one-fourth from

private study, one-fourth from one's fellows, and one-fourth from life." "Every village had its schoolmaster, supported out of the public funds; in Bengal

alone, before the coming of the British, there were some 80,000 native schools -

one to every four hundred population. Instruction was given to him in the

"Five Shastras" or sciences: grammar, arts and crafts, medicine, logic

and philosophy. Finally the child was sent out into the world with the wise

admonition that education came only one-fourth from the teacher, one-fourth from

private study, one-fourth from one's fellows, and one-fourth from life."

(source:

Story

of Civilization: Our Oriental Heritage - By Will Durant

MJF Books.1935 p.556-557).

Christian

missionaries and the British are also proud that they brought

education to India, "but," counters Sri Sri Ravi

Shankar, Founder of the

Bangalore based Art of Living, an International Foundation. He recently

addressed the UN Peace Summit on Aug 28. He is the only non-westerner to serve

on the advisory board of Yale University's School of Divinity and is author of

the book - Hinduism and Christianity:

"it is not true: there were for instance 125,000 medical

institutions in Madras before the British came. Indians never lacked

education, the Christians only brought British education to India,

which in fact caused more damage to India by westernizing many of

us."

Sir

John Woodroffe,

(1865-1936) the well known scholar, Advocate-General of Bengal and sometime

Legal Member of the Government of India. Referring

to the Macaulay's Educational Minute of 1834

(for education refer to chapter on Hindu

Culture Education

in Ancient India and First

Indologists)

he wrote:

"To

an Indian, self-conscious of the greatness of his country's civilization, it

must be gall and wormwood to hear others speaking of the "education"

and "civilization" of India. India who has taught some of the deepest

truths which our race has known is to be 'educated.' She whose ancient

civilization ranks with the greatest the world has known is to be

civilized."

(source: Is

India Civilized: Essays on Indian Culture - By Sir John Woodroffe

p.290).

European

travelers and administrators bear testimony to the great veneration in which

Hindus held learning and instruction. One of the earliest observation

was made on the subject of indigenous education was by Fra

Paolino Da Bartolomeo. Born in Austria, he spent 14 years in India

(1776-1789). He wrote: "No people, perhaps, on earth have adhered as much

to their ancient usage and customs as the Indians." and "temperance

and education contribute, in an uncommon degree, to the bodily confirmation, and

to the increase of these people."

Brigadier-General

Alexander Walker who served in India between 1780-1810, says, that "no

people probably appreciate more justly the importance of instruction that the

Hindus."

The fact of

wide-spread

education - a school in every village - was uniformly noticed by most early

observers. Even writing as late as 1820, Abbe

J. A. Dubois says that "there are very few villages in which one

or many public schools are not to be found...that the students learn in them all

that is necessary to their ranks and wants...namely, reading, writing and

accounts."

(source: On

Hinduism Reviews and Reflections - By Ram Swarup p. 179-180 -

refer to chapter on Hindu

Culture for more information on Education in Ancient

India).

In

October 1931 Mahatma Gandhi made a statement

at Chatham House, London, that created a furore in the English press. He said,

"Today India is more illiterate than it was fifty or a hundred years ago,

and so is Burma, because the British administrators, when they came to India,

instead of taking hold of things as they were, began to root them out. They

scratched the soil and left the root exposed and the beautiful tree

perished". Mahatma Gandhi said,

"The beautiful tree of education was cut down by you British. Therefore

today India is far more illiterate than it was 100 years ago." We

now learn, with almost a sense of disbelief, that a large part of the country

did have a sustainable education system, as late as even the early years of the

19th century, and that this was systematically demolished over the next 50 years

or so. The present education system is, in effect, a legacy of the colonial

rule. This system has perpetuated the notion that traditional societies were

seeped in ignorance, superstition and rituals for thousands of years and lived a

life of abject poverty, which was caused by an extreme form of social

discrimination and exploitative socio-political systems. So deep has this notion

seeped into our collective consciousness that, it colors the belief of both,

providers of education as well as of recipients and aspiring recipients in our

society. In

October 1931 Mahatma Gandhi made a statement

at Chatham House, London, that created a furore in the English press. He said,

"Today India is more illiterate than it was fifty or a hundred years ago,

and so is Burma, because the British administrators, when they came to India,

instead of taking hold of things as they were, began to root them out. They

scratched the soil and left the root exposed and the beautiful tree

perished". Mahatma Gandhi said,

"The beautiful tree of education was cut down by you British. Therefore

today India is far more illiterate than it was 100 years ago." We

now learn, with almost a sense of disbelief, that a large part of the country

did have a sustainable education system, as late as even the early years of the

19th century, and that this was systematically demolished over the next 50 years

or so. The present education system is, in effect, a legacy of the colonial

rule. This system has perpetuated the notion that traditional societies were

seeped in ignorance, superstition and rituals for thousands of years and lived a

life of abject poverty, which was caused by an extreme form of social

discrimination and exploitative socio-political systems. So deep has this notion

seeped into our collective consciousness that, it colors the belief of both,

providers of education as well as of recipients and aspiring recipients in our

society.

(source: http://www.indiatogether.org/education/opinions/btree.htm).

(For more please refer to noted

Gandhian, Dharampal's book. The

Beautiful Tree, (Biblia Impex, Delhi, 1983}.

When

the British came there was, throughout India, a system of communal schools,

managed by the village communities. The agents of the East India Company

destroyed these village communities, and took steps to replace the schools; even

today, after a century of effort to restore them, they stand at only 66% of

their number a hundred years ago. Hence, the 93 % illiteracy of India.

(source:

The

Case for India - By Will Durant Simon and Schuster,

New York. 1930 p.44).

Mr. Ermest Havell

(formerly Principal of the Calcutta school of Art) has rightly said, the fault

of the Anglo-Indian Educational System is that, instead of harmonizing with, and

supplementing, national culture, it is antagonist to, and destructive, of it.

Sir George Birdwood says

of the system that it “has destroyed in Indians the love of their own

literature, the quickening soul of a people, and their delight in their own

arts, and worst of all their repose in their own traditional and national

religion, has disgusted them with their own homes, their parents, and their

sisters, their very wives, and brought discontent into every family so far as

its baneful influences have reached.

(source:

Bharata Shakti: Collection of Addresses on Indian

Culture - By Sir John Woodroffe p.

75-77).

The

missionaries and the government cooperated for mutual benefit in the spread of

Western education. The government made use of the linguistic

expertise of the missionaries and their knowledge of local customs and tradition

for the extension and consolidation of the empire. By the middle of the 19th

century a new type of English rulers was emerging. The evangelical influence had

grown and the new officials both in London and in India made no secret of their

sincere profession of Christianity. Some of the British officials including

Governors like Bartle Frere of Bombay

(1862-1868) openly supported the missionary work. Voicing a similar sentiment, Lord

Lawrence, Viceroy and Governor-General of India (1864-1869) stated,

"I believe not withstanding all that the English people have done to

benefit the country, the Missionaries have done more than all other agencies

combined." After 1860 there was not only an increase in the number of

missionaries who came to India but the number of Indian Christians also went

up.

(source: Western

Colonialism in Asia and Christianity - edited by Dr. M.D. David

p. 88-89).

The

new rulers were understandably hostile to the indigenous education system.

As soon as the British took over the Punjab, the Education Report of 1858 says:

" A village school left to itself is not an institution which we have any

great interest in maintaining."

This

hostility arose partly from a lack of imagination. To the new rulers, brought up

so differently, a school was no school if it did not teach English.

(source:

On

Hinduism Reviews and Reflections - By Ram Swarup p. 191-192).

For more on education please refer below to article

- Education in India

Under the East India Company - Major B. D. Basu).

Another

design which the British evolved to promote Christianization of India was T.B.

Macaulay’s educational system introduced in 1835. “It

was the devout hope of Macaulay… and of many others, that the diffusion of new

learning among the higher classes would see the dissolution of Hinduism and the

widespread acceptance of Christianity. The missionaries were of

the same view, and they entered the education field with enthusiasm, providing

schools and colleges in many parts of India where education in the Christian

Bible was compulsory for Hindu students. The

Grand Design on which “they had spent so much money and energy had failed”.

The rise of Indian nationalism also had an adverse effect on missionary

fortunes. The great leaders of the national movement such as Lokmanya

Tilak, Sri Aurobindo and Lala Lajpat Rai were champions of resurgent Hinduism.

(source:

Vindicated

by Time: The

Niyogi Committee Report On Christian Missionary Activities

- By

Sita Ram Goel).

Dr. Ananda K

Coomaraswamy (1877-1947) the

late curator of Indian art at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, and author of The

Dance of Shiva: Essays on Indian Art and Culture, wrote:

"One of the most remarkable

features of British rule in India has been the fact that the greatest injuries

done to the people of India have taken the outward form of blessings. Of this,

Education is a striking example; for no more crushing blows have ever been

struck at the roots of Indian evolution than those which have been

struck..." It is sometimes said by friends of India that the National

movement is the natural result by English education, and one of which England

should in truth be proud, as showing that, under 'civilization' and the Pax

Britannica, Indians are becoming, at last, capable of self-government. The facts

are all the anti-national tendencies of a system of education that has ignored

or despised almost every ideal informing the national culture." "One of the most remarkable

features of British rule in India has been the fact that the greatest injuries

done to the people of India have taken the outward form of blessings. Of this,

Education is a striking example; for no more crushing blows have ever been

struck at the roots of Indian evolution than those which have been

struck..." It is sometimes said by friends of India that the National

movement is the natural result by English education, and one of which England

should in truth be proud, as showing that, under 'civilization' and the Pax

Britannica, Indians are becoming, at last, capable of self-government. The facts

are all the anti-national tendencies of a system of education that has ignored

or despised almost every ideal informing the national culture."

"Yes, English educators of

India, you do well to scorn the Babu graduate; he is your own special

production, made in your own image; he might be one of your very selves. Do you

not recognize the likeness? Probably you do not; for

you are still hidebound in that impervious skin of self-satisfaction that

enabled your most pompous and self-important philistine, Lord Macaulay,

to believe that a single shelf of a good European library was worth all the

literature of India, Arabia, and Persia. Beware lest in a hundred years the

judgment be reversed, in the sense that Oriental culture will occupy a place

even in European estimation, ranking at least equally with Classic. Meanwhile

you have done well nigh all that could be done to eradicate it in the land of

the birth."

"A single

generation of English education suffices to break the threads of tradition and

to create a nondescript and superficial being deprived of all roots - a sort of

intellectual pariah who does not belong to the East or West, the past or the

future."

(source: The

Wisdom of Ananda Coomaraswamy - presented by S. Durai Raja Singam

1979 p. 38-40). For more on education, refer to chapter on Education

in Ancient India and Hindu

Culture II).

"British-educated Indians grew

up learning about Pythagoras, Archimedes, Galileo and Newton without ever

learning about Panini, Aryabhatta, Bhaskar or Bhaskaracharya. The logic

and epistemology of the Nyaya Sutras, the rationality of the early Buddhists or

the intriguing philosophical systems of the Jains were generally unknown to the

them. Neither was there any awareness of the numerous examples of dialectics in

nature that are to be found in Indian texts. They may have read Homer or Dickens

but not the Panchatantra, the Jataka tales or anything from the Indian epics.

Schooled in the aesthetic and literary theories of the West, many felt

embarrassed in acknowledging Indian contributions in the arts and literature.

What was important to Western civilization was deemed universal, but everything

Indian was dismissed as either backward and anachronistic, or at best tolerated

as idiosyncratic oddity. Little did the Westernized Indian know what debt

"Western Science and Civilization" owed (directly or indirectly) to

Indian scientific discoveries and scholarly texts.

Dilip

K. Chakrabarti (Colonial Indology)

thus summarized the situation:

"The model of the Indian past...was foisted on Indians by the hegemonic

books written by Western Indologists concerned with language, literature and

philosophy who were and perhaps have always been paternalistic at their best and

racists

at their worst.."

Elaborating

on the phenomenon of cultural colonization, Priya Joshi

(Culture

and Consumption: Fiction, the Reading Public, and the British Novel in Colonial

India) writes: "Often, the implementation of a new education

system leaves those who are colonized with a lack of identity and a limited

sense of their past. The indigenous history and customs once practiced and

observed slowly slip away. The colonized become hybrids of two vastly different

cultural systems. Colonial education creates a blurring that makes it difficult

to differentiate between the new, enforced ideas of the colonizers and the

formerly accepted native practices."

Ngugi

Wa Thiong'o, (Kenya, Decolonising the Mind),

displaying anger toward the isolationist feelings colonial education causes,

asserted that the process "...annihilates a peoples belief in their names,

in their languages, in their environment, in their heritage of struggle, in

their unity, in their capacities and ultimately in themselves. It makes them see

their past as one wasteland of non-achievement and it makes them want to

distance themselves from that wasteland. It makes them want to identify with

that which is furthest removed from themselves".

Strong

traces of such thinking continue to infect young Indians, especially those that

migrate to the West. Elements of such mental insecurity and alienation also had

an impact on the consciousness of the British-educated Indians who participated

in the freedom struggle. In contemporary academic circles, various false

theories continue to percolate. While some write as if Indian civilization

has made no substantial progress since the Vedic period, for others the clock

stopped with Ashoka, or with the "classical age" of the Guptas.

Mahatma

Gandhi wrote in the "Harijan:

"That Indian education made Indian students foreigners in their own country. The

Radhakrishnan Commission said in their Report (1950); "one of the serious

complaints against the system of education which has prevailed in this country

for over a century is that it neglected India's past, that it did not provide

the Indian students with a knowledge of their own culture. It had produced in

some cases the feeling that we are without roots, and what is worse, that our

roots bind us to a world very different from that which surrounds us".

(source:

British

Education in India - By Dr David Grey).

***

Debunking Myth:

Dalits and Indigenous System of Educaiton

Dharampal

(The Beautiful Tree) has effectively

debunked the myth that Dalits had no place in the indigenous system of

education. Sir Thomas Munro, Governor of Madras, ordered a mammoth

survey in June 1822, whereby the district collectors furnished the caste-wise

division of students in four categories, viz., Brahmins, Vysyas (Vaishyas),

Shoodras (Shudras) and other castes (broadly the modern scheduled castes). While

the percentages of the different castes varied in each district, the results

were revealing to the extent that they showed an impressive presence of the

so-called lower castes in the school system.

Thus, in Vizagapatam, Brahmins and Vaishyas together accounted for 47% of the

students, Shudras comprised 21% and the other castes (scheduled) were 20%; the

remaining 12% were Muslims. In Tinnevelly, Brahmins were 21.8% of the total

number of students, Shudras were 31.2% and other castes 38.4% (by no means a low

figure). In South Arcot, Shudras and other castes together comprised more than

84% of the students!

In the realm of higher education as well, there were regional variations.

Brahmins appear to have dominated in the Andhra and Tamil Nadu regions, but in

the Malabar area, theology and law were Brahmin preserves, but astronomy and

medicine were dominated by Shudras and other castes. Thus, of a total of 808

students in astronomy, only 78 were Brahmins, while 195 were Shudras and 510

belonged to the other castes (scheduled). In medicine, out of a total of 194

students, only 31 were Brahmins, 59 were Shudras and 100 belonged to the other

castes. Even subjects like metaphysics and ethics that we generally associate

with Brahmin supremacy, were dominated by the other castes (62) as opposed to

merely 56 Brahmin students. It bears mentioning that this higher education was

in the form of private tuition (or education at home), and to that extent also

reflects the near equal economic power of the concerned groups.

As a concerned reader informed me, the ‘Survey of Indigenous Education in the

Province of Bombay (1820-1830)’ showed that Brahmins were only 30% of the

total students there. What is more, when William Adam surveyed Bengal and Bihar,

he found that Brahmins and Kayasthas together comprised less than 40% of the

total students, and that forty castes like Tanti, Teli, Napit, Sadgop, Tamli

etc. were well represented in the student body. The Adam report mentions that in

Burdwan district, while native schools had 674 students from the lowest thirty

castes, the 13 missionary schools in the district together had only 86 students

from those castes. Coming to teachers, Kayasthas triumphed with about 50% of the

jobs and there were only six Chandal teachers; but Rajputs, Kshatriyas and

Chattris (Khatris) together had only five teachers.

Even Dalit intellectuals have questioned what the

British meant when they spoke of ‘education’ and ‘learning’. Dr. D.R.

Nagaraj, a leading Dalit leader of Karnataka, wrote that it was the British,

particularly Lord Wellesley, who declared the Vedantic Hinduism of the Brahmins

of Benares and Navadweep as “the standard Hinduism,” because they realized

that the vitality of the Hindu dharma of the lower castes was a threat to the

empire. Fort William College, founded by Wellesley in 1800, played a

major role in investing Vedantic learning with a prominence it probably hadn't

had for centuries. In the process, the cultural heritage of the lower castes was

successfully marginalized, and this remains an enduring legacy of colonialism.

Examining Dharampal's “Indian science and technology in the eighteenth

century,” Nagaraj observed that most of the native skills and technologies

that perished as a result of British policies were those of the Dalit and

artisan castes. This effectively debunks the fiction of

Hindu-hating secularists that the so-called lower castes made no contribution to

India's cultural heritage and needed deliverance from wily Brahmins.

Indeed, given the desperate manner in which the British vilified the Brahmin, it

is worth examining what so annoyed them. As early as 1871-72, Sir John Campbell

objected to Brahmins facilitating upward mobility: “…the Brahmans are always

ready to receive all who will submit to them… The process of manufacturing

Rajputs from ambitious aborigines (tribals) goes on before our eyes.”

Sir

Alfred Lyall (1796 - 1865) was unhappy that: Sir

Alfred Lyall (1796 - 1865) was unhappy that:

“…more

persons in India become every year Brahmanists than all the converts to all the

other religions in India put together... these teachers address themselves to

every one without distinction of caste or of creed; they preach to low-caste men

and to the aboriginal tribes… in fact, they succeed largely in those ranks of

the population which would lean towards Christianity and Mohammedanism if they

were not drawn into Brahmanism…”

So much for the

British public denunciation of the exclusion practiced by Brahmins!

(source: The Brahmin and the Hindu - By Sandhya Jain -

dailypioneer.com - December 14 2004).

Thus,

the British education system also was at the root of weakening the foundations

of Hinduism or Indian nationalism. This was foreseen by some founders of British

educational system.

***

3. Unity - Sense of

belonging:

Mahatma Gandhi,

(1869-1948) was among India's most fervent

nationalists, fighting for Indian independence from British rule. He wrote in his book, Hindu Swaraj: "The English have taught us that we

were not one nation before and that it will require centuries before we become

one nation. This is without foundation. We were one

nation before they came to India. One thought inspired us. Our mode

of life was the same. It was because we were one nation that they were able to

establish one kingdom. Subsequently they divided us." What do you

think could have been the intention of those farseeing

ancestors of ours who established Setubandha (Rameshwar) in the

South, Jaganath in the East and Hardwar in the North as places of pilgrimage?

You will admit they were no fools. They knew that worship of God could have been

performed just as well at home. They taught us that those whose hearts were

aglow with righteousness had the Ganges in their own homes. But

they saw that India was one undivided land so made by nature." They,

therefore, argued that it must be one nation. Arguing thus, they established

holy places in various parts of India, and fired the people with an idea of

nationality in a manner unknown in other parts of the world. "

(source: Hindu

Swaraj or Indian Home Rule - By M. K. Gandhi p. 46).

Bipin

Chandra Pal (1858-1932) freedom fighter

and lawyer, wrote: "The European and the American come to India with a

strong prepossession, and cannot discover any fundamental principle of unity at

the back of the many bewildering diversities......Every

Anglo-Indian publicist assiduously proclaims that India is not a country

but a collection of countries, which have as little or as much in common with

one another, either in race or history, as the German, the French, the Dutch,

the Russian, the Italian, the English and the Spaniard in Europe have between

them.....The orthodox official view is, in any case, there never was such an

animal as Indian, until the British rulers of the country commenced so

generously to manufacture him with the help of their schools and their colleges,

their courts and their camps, their law and their administration." Bipin

Chandra Pal (1858-1932) freedom fighter

and lawyer, wrote: "The European and the American come to India with a

strong prepossession, and cannot discover any fundamental principle of unity at

the back of the many bewildering diversities......Every

Anglo-Indian publicist assiduously proclaims that India is not a country

but a collection of countries, which have as little or as much in common with

one another, either in race or history, as the German, the French, the Dutch,

the Russian, the Italian, the English and the Spaniard in Europe have between

them.....The orthodox official view is, in any case, there never was such an

animal as Indian, until the British rulers of the country commenced so

generously to manufacture him with the help of their schools and their colleges,

their courts and their camps, their law and their administration."

"But while the stranger called

her India, her own children, from of old, have known and loved her by another

name. We never called her India. Long before the Greek invasion and even before

the Babylonians and Assyrians came in any sort of contact with us, we had given

this name of our country. That name is Bharatvarsha. Those who so persistently

deny any fundamental historic unity or any real national individuality to our

land and our people, either do not know, or they do not remember the fact that

we never called our country by the alien name of India or even by that of

Hindoostan. Our own name was, is still today, Bharatvarsha. But Bharatvarsha is

not physical name, but a distinct and unmistakable historic name... Bharata was

a king. He is a Vedic personage. The limit of Bharatvarsha extended in those

days even much further than the present limits of India.

The unity of India was neither

racial nor religious, nor political nor administrative. It was a peculiar type

of unity, which may, perhaps, be best described as cultural."

(source: The

Soul of India - By Bipin Chandra Pal Published by Choudhury

& Choudhary Calcutta 1911. p. 84-98).

The British deliberately tried to

create a kind of pychosis among the Indians that India has always

been subject to foreign invasions and internal feuds, that there has been no

political unity in India at any time, that the cultural unity of India was a

fiction, and that whatever was good in India was due to European influence. The

British historian firmly believed that the British had a mission to fulfill in

India, and that the British rule was a blessing for India.

(source:

Recent Historiography of Ancient India - By Shankar

Goyal p. 422).

Although the Raj claimed the credit

for India’s political unification, the sub-continent had a geo-political unity

that dated back 2000 years before the British conquest to the Hindu-Buddhist

Mauryan empire. The Maurya emperors had united most of the

sub-continent under their rule between the fourth and second centuries BC; and

their imperial ideal was echoed from the fourth to sixth centuries AD by a later

Hindu dynasty the Guptas.

(source:

Indian

Tales of the Raj - By Zareer Masani p. 7).

Perhaps the most mischievous

statement we have of the claim that India has no unity, it is not a nation,

is made by Sir John Strachey on the

opening page of his well-known book, “India”. There he says:

“The first and most essential thing to be learned about

India, is that there is not and never was an India possessing according to

European ideas any sort of unity, physical, social, political, or religious: no

Indian nation, no people of India of which we hear so much.”

This alleged condition of things he claims to be a clear

justification of British rule. What answer is to be made? Sir

Ramsey Macdonald, at one time Premier declares that India is one in

absolutely every sense in which Mr. Strachey denies the unity. Here are his

words:

“India from the Himalayas to Cape Comorin, from the Bay of

Bengal to Bombay, is naturally the area of a single government. One has only to

look at the map to see how geography has fore-ordained an Indian Empire. Its

vastness does not obscure its oneness; its variety does not hide from view its

unity. The Himalayas and their continuing barriers frame off the great peninsula

from the rest of Asia. Its long rivers, connecting its extremities and its

interior with the sea, knit it together for communication and transport

purposes; its varied productions, interchangeable with one another, make it a

convenient industrial unit, maintaining contact with the world through the great

ports to the east and west. Political and religious

traditions have also welded it into one Indian consciousness. This spiritual

unity dates from very early times in Indian culture. An historical atlas of India shows how again and again the

natural unity of India has influenced conquest and showed itself, its empires.

The realms of Chandragupta and his grandson Asoka embraced practically the whole

peninsula, and ever after, amidst the swaying and falling of dynasties, this

unity has been the dream of every victor and has never lost its potency.”

Says British historian Vincent Smith, than

whom there is no higher historical authority, in his book Early History of

India:

“India circled as she is by seas and mountains, is

indisputably a geographical unit, and as such rightly designated by one name.

Her type of civilization, too, has many features which differentiate it from

that of all other regions of the world; while they are common to the whole

country in a degree sufficient to justify its treatment as a unit in the history

of the social religious, and intellectual development of mankind.”

William

Archer in his “India and the Future” devotes a chapter to “The

Unity of India” in which he declares that Indian unity is “indisputable.”

There is no greater uniting force

known among people and nations in the world than religion. This applies with

pre-eminent emphasis to India.

(source: India

in Bondage: Her Right to Freedom - Rev. Jabez T. Sunderland

p. 238-289

Hinduism

has imparted to the whole of India a strong and stable cultural unity that has

through the ages stood the shocks of political revolutions.

James Ramsey MacDonald

(1866 -1937) first Labor Party prime minister of Great Britain could grasp this

truth when he said:

"The Hindu from his traditions and religion

regards India not only as a political unit naturally the subject of one

sovereignty, but as the outward embodiment, as the temple - nay even as the

Goddess Mother of his spiritual culture. "India

and Hinduism are organically related as body and soul."

(source: The

Soul of India - By Satyavrata R Patel p.208).

Political Unity

of India since Ancient Times

The name

Bharatvarsha has a deep historical significance, symbolizing, a fundamental

unity. The term was associated not only with the geographical

boundaries but also with the idea of universal monarchy. The term was associated

not only with the geographical boundaries but also with the idea of universal

monarchy. This name together with the sense of unity imparted by it "was

ever present before the mind of the theologians, political philosophers and

poets who spoke of the thousand Yojanas (Leagues) of land that stretches from

the Himalayas to the sea as the proper domain of a single universal

emperor".

An early hymn in the Arthaveda,

in a salutation to Mother Earth, expresses the same sentiment arising out of the

enchantment of the land. Thus the very Indian land became an embodiment of the

yearning for the Beyond. This deep-rooted sentiment is given expression to in

the Vishnu-Purana. "Bharata is the best

of the divisions of Jambudwipa (Asia) because it is the land of virtuous deeds.

Other countries seek only enjoyment. Happy are those who, consigning all the

rewards of their deeds to the Supreme Spirit, the Universal Self, pass their

lives in this land of virtuous deeds, as the means of realization of Him. The

gods exclaim, "Happy are those who are born, even from the condition of

divinity, as men in Bharatvarsha, as that is the path of the joys of paradise

and the greater blessings of final liberation." Another book, the Bhagvat

Purana states, "Here God Himself in His grace is born as man to

obtain the fervent devotion of sentient beings, so that they may wish final

liberation. Even the gods prefer birth in this sacred land to enjoyment in

heaven, won by so much sacrifice, penance and charity. This basic concept of

India (Bharat) and spirituality (dharma) are identical and the faith that

neither dharma nor its favored homeland can perish, in spite of the misfortunes

of history, gave the people the confidence to survive the storms of political

life or convulsions of nature through the millenniums.

(source: The

Soul of India - By Satyavrata R Patel p.206-210).

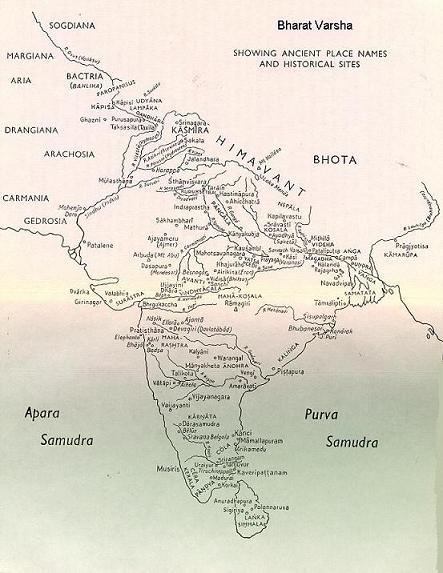

Bharat Mata: Mother India - By

Abanindranath Tagore's watercolor

(image source: Indian Art - By Vidya

Dehejia).

This is what is stated in an

inscription of King Yasodharman of Mandasor, Successors

of the Guptas in the North:

"From the lands where the

Brahmaputra flows,

from the flanks of the southern hills, thick with grove of palms,

from the snowy mountains whose peak the Ganga clasps,

and from the ocean of the West,

come vassals, bowing at his feet,

their pride brought low by his mighty arm,

and his palace court is a glitter,

with the bright jewels of their turban."

The rulers of medieval India also

considered India as one geographical unit and sought to extend their sway over

the whole of the land. The song Vandematram embodies

that sense of unity.

There is also an

under-current of religious unity among the various religious sects in the

country. That is partly due to the overwhelming impact of Hinduism on the Indian

mind which transcends any other single religion. This is mainly due to the

comprehensive and all-embracing pervasiveness of Hinduism. Hinduism is not a

mere form of religious approach or system. It is a "mosaic of almost all

types and stages of religious aspiration and endeavor."

(source: Ancient

India - By V. D. Mahajan p. 15).

The unifying effect of Hinduism and

Sanskritic culture was great. Records dating from the early centuries indicate

that shrines regarded sacred by all Hindus were located at widely separated

points in all directions. Clearly, some concept of religious and cultural unity

already existed. Long pilgrimages to such shrines created for many a connection

with peoples in areas under different sovereignties. Then, too, the great body

of Sanskritic literature provided a significant bond.

(source: India:

A World in Transition - By Beatrice Pitney Lamb

p. 32).

According to Jawaharlal

Nehru: "Right from

the beginning, culturally India has been one, because she had the same

background, the same traditions, the same religions, the same heroes and

heroines, the same old tales, the same learned language (Sanskrit), the village

panchayats, the same ideology, and polity. To the average Indian the whole of

India was a kind of punya-bhumi

- a holy land - while

the rest of the world was largely peopled by mlechchhas and barbarians.

Sankaracharya

chose the four corners of India for his maths,

or the headquarters of his order of sanyasins, shows how he regarded India as a

cultural unit. And the great success which met his campaign all over the country

in a very short time also shows how intellectual and cultural currents traveled

rapidly from one end of the country to another."

(source: Glimpses

of World History - By Jawaharlal Nehru

p. 129).

Uttaram yat samudrasya

Himadreschaiva dakshinam..Varsham tad Bharatam nama Bharati yatra santatih.

(The country that lies north of

the ocean and south of the Himalayas is called Bharata; there dwell the

descendents of Bharata - Vishnu Purana, II, 3. 1-

(image source: Ancient Indian History

and Culture - By Chidambara Kulkarni p. 4).

***

Dr. Radhakrishnan: "In spite of the divisions, there is an inner cohesion among the Hindu society

from the Himalayas to the Cape Comorin."

(source: The

Hindu View of Life - By Sir. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan

p. 73-77).

Girilal Jain,

late editor of Times of India: " It is about time we recognize that we are

not a nation in the European sense of the term, that is, we are not a fragment

of a civilization claiming to be a nation on the basis of accidents of history

which is what every major European nation is. We are a people primarily

by virtue of the continuity and coherence of our civilization which has survived

all shocks. And though inevitably weakened as a result of foreign invasions,

conquests and rule for almost a whole millennium, it is once again ready to

resume its march."

(source: Hindu

Phenomenon - By Girilal Jain

p. 21).

Sri Aurobindo

has said: "In India at a very early time: the

spiritual and cultural unity was made complete and became the very

stuff of the life of all this great surge of humanity between the Himalayas and

the two seas....Invasion and foreign rule, ....the enormous pressure of the

Occident have not been able to drive or crush the

ancient soul out of the body her Vedic Rishis made for her." Sri Aurobindo

has said: "In India at a very early time: the

spiritual and cultural unity was made complete and became the very

stuff of the life of all this great surge of humanity between the Himalayas and

the two seas....Invasion and foreign rule, ....the enormous pressure of the

Occident have not been able to drive or crush the

ancient soul out of the body her Vedic Rishis made for her."

(source: India's Rebirth

- By Sri Aurobindo pg 158).

Guy Sorman

visiting scholar at Hoover Institution at Stanford and the leader of new

liberalism in France, says that the idea of a nation-state was an 18th century creation of the West.

It is the cultural identity that has helped India stay together. The

British did not do it for the love of India. It was here that the West started

to colonize what was to become the Third World, a shameless process of

systematic exploitation without any moral or religious justification.

(source: The

Genius of India

- By Guy Sorman ('Le Genie de

l'Inde') p. 197).

N. S.

Rajaram: "It was claimed by the British, and faithfully repeated by the

Leftist intellectuals, that the British unified India. This is

completely false. The unity of India, rooted in her

ancient culture, is of untold antiquity.

It may have been divided at

various times into smaller kingdoms, but the goal was always to be united under

a ‘Chakravartin’ or a ‘Samrat’. This unity was cultural though not

always political. This cultural unity was seriously damaged during the Medieval

period, when India was engaged in a struggle for survival — like what is

happening in Kashmir today. Going back thousands of years, India had been united

under a single ruler many times. The earliest recorded emperor of India was

Bharata, the son of Shakuntala and Dushyanta, but there were several others. I

give below some examples from the Aitareya Brahmana. "With this great

anointing of Indra, Dirghatamas Mamateya anointed Bharata Daushanti.

Therefore, Bharata Daushanti went round the earth completely, conquering on

every side and offered the horse in sacrifice. "With this great anointing

of Indra, Tura Kavasheya anointed Janamejaya Parikshita. Therefore Janamejaya

Parikshita went round the earth completely, conquering on every side and

offered the horse in sacrifice."

There are similar statements

about Sudasa Paijavana anointed by Vasistha, Anga anointed by Udamaya Atreya,

Durmukha Pancala anointed by Brihadukta and Atyarati Janampati anointed by

Vasistha Satyahavya. Atyarati, though not born a king, became an emperor and

went on conquer even the Uttara Kuru or the modern Sinkiang and Turkestan that

lie north of Kashmir. There are others also mentioned in the Shathapatha

Brahmana and also the Mahabharata. This shows that the unity of India

is ancient. Also, the British did not rule over a unified India. They had

treaties with the rulers of hereditary kingdoms like Mysore, Kashmir, Hyderabad

and others that were more or less independent. The person who united all these

was Sardar Patel, not the British. But this unification was possible only

because India is culturally one. Pakistan, with no such identity or cultural

unity, is falling apart.

(source: Distortions in

Indian History http://www.voi.org/books/dist/ch2.htm#3 ).

For more on the myths of British Raj, refer to The

Colonial Legacy - Myths and Popular Beliefs - By Dr David Grey).

The British rule

often claim to have given India - Democracy. If

so, Why did it take

200 years to give India Democracy?

For more read:

Democracy

in Ancient India

- By

Steve

Muhlberger

Sri Jayendra Saraswati - The

Sankaracharya of Kanchi

has said: Sri Jayendra Saraswati - The

Sankaracharya of Kanchi

has said:

"The British never created

anything in India - they merely destroyed. Instead of uniting, they divided; so

the question is meaningless. For five thousand years Hindus have chanted in

their morning prayers:

"Gange

cha Yamunechaiva! Godavari! Sarasvati!

Narmade! Sindhu! Kaveri! Jale asmin sannidhim kuru!"

"Hail!

O ye Ganges, Jamuna, Godavari, Sarasvati, Narmada,

Sindhu and Kaveri, come and approach these waters."

There has been an explicit and clear

geographical area that we have referred to as our land. Adi Sankara not only

went to the four corners of this territory, he set up tens of shrines all over

the Hindu land to be able to revive and revitalize Hinduism. It is absurd to

think that India is a new idea."

(source: Interview with Sri Jayendra Saraswati - by

Rajeev Srinivasan - India Abroad March 8'2002).

***

The

Colonial Legacy - Myths and Popular Beliefs

While few educated South Asians would deny that British Colonial rule was

detrimental to the interests of the common people of the sub-continent - several

harbor an illusion that the British weren't all bad. Didn't they, perhaps,

educate us - build us modern cities, build us irrigation canals - protect our

ancient monuments - etc. etc.

Literacy

and Education

The

literacy in

British India

in 1911 was only 6%, in 1931 it was 8%, and by 1947 it had crawled to 11%!

Urban

Development

It

is undoubtedly true that the British built modern cities with modern

conveniences for their administrative officers. But it should be noted that

these were exclusive zones not intended for the "natives" to enjoy.

Consider that in 1911, 69 per cent of

Bombay

's population lived in one-room tenements (as against 6 per cent in

London

in the same year).

After

the Second World War, 13 per cent of

Bombay

's population slept on the streets. As for sanitation, 10-15 tenements typically

shared one water tap! It

is undoubtedly true that the British built modern cities with modern

conveniences for their administrative officers. But it should be noted that

these were exclusive zones not intended for the "natives" to enjoy.

Consider that in 1911, 69 per cent of

Bombay

's population lived in one-room tenements (as against 6 per cent in

London

in the same year).

After

the Second World War, 13 per cent of

Bombay

's population slept on the streets. As for sanitation, 10-15 tenements typically

shared one water tap!

Yet, in 1757

(the year of the Plassey defeat), Robert Clive

of the East India Company

had observed of Murshidabad in Bengal:

"This

city is as extensive, populous and rich as the city of

London

..."

(so quoted in the Indian Industrial Commission Report of 1916-18). Dacca

was even more famous as a manufacturing town, it's muslin a source of many

legends and it's weavers had an international reputation that was unmatched in

the medieval world.

But in 1840 it was reported by Sir

Charles Trevelyan

(1807 - 1886) to a parliamentary enquiry that Dacca

's population had fallen from 150,000 to 20,000.

Montgomery

Martin - an early historian of the British Empire observed that

Surat

and Murshidabad had suffered a similiar fate. (This phenomenon was to be

replicated all over India - particularly in Awadh (modern U.P) and other areas

that had offered the most heroic resistance to the British during the revolt of

1857.)

In 1854, Sir

Arthur Cotton

(1803 - 1899) writing in "Public Works in

India

" noted: In 1854, Sir

Arthur Cotton

(1803 - 1899) writing in "Public Works in

India

" noted:

"Public

works have been almost entirely neglected throughout India

... The motto hitherto has been: 'Do nothing, have nothing done, let nobody do

anything....."

Adding that the Company was unconcerned if people died

of famine, or if they lacked roads and water. Nothing can be more revealing than the remark by

John Bright in the

House of

Commons on June 24, 1858,

"The single city of Manchester, in the supply

of its inhabitants with the single article of water, has spent a larger sum of

money than the East India Company has spent in the fourteen years from 1834 to

1848 in public works of every kind throughout the whole of its vast dominions."

Irrigation

and Agricultural Development

There

is another popular belief about British rule: 'The British modernized Indian

agriculture by building canals'. But the actual record reveals a somewhat

different story.

"

The roads and tanks and canals," noted an observer in 1838 (G.

Thompson, "India and the Colonies," 1838), ''which Hindu or

Mussulman Governments constructed for the service of the nations and the good of

the country have been suffered to fall into dilapidation; and now the want of

the means of irrigation causes famines."

Robert

Montgomery

Martin,

in his standard work "The

Indian Empire",

in 1858, noted that the old East India Company

"omitted not only to

initiate improvements, but even to keep in repair the old works upon which the

revenue depended."

Sir

William Willcock

(1852 - 1932) a distinguished hydraulic engineer, whose name was associated with

irrigation enterprises in

Egypt

and Mesopotamia had made an investigation of conditions in

Bengal. He wrote: Sir

William Willcock

(1852 - 1932) a distinguished hydraulic engineer, whose name was associated with

irrigation enterprises in

Egypt

and Mesopotamia had made an investigation of conditions in

Bengal. He wrote:

"Not only was nothing done to utilize and improve the original canal system,

but railway embankments were subsequently thrown up, entirely destroying it.

Some areas, cut off from the supply of loam-bearing

Ganges

water, have gradually become sterile and unproductive, others improperly

drained, show an advanced degree of water-logging, with the inevitable

accompaniment of malaria. Nor has any attempt been made to construct proper

embankments for the Gauges in its low course, to prevent the enormous erosion by

which villages and groves and cultivated fields are swallowed up each year."

Modern

Medicine and Life Expectancy

Even

some serious critics of colonial rule grudgingly grant that the British brought

modern medicine to

India

. Yet - all the statistical indicators show that access to modern medicine was

severely restricted. A 1938 report by the ILO (International Labor Office) on

"Industrial Labor in

India

" revealed that life expectancy in

India

was barely 25 years in 1921 (compared to 55 for England) and had actually fallen to 23 in 1931! In his recently published "Late

Victorian Holocausts"

Mike Davis reports that life expectancy fell by

20% between 1872 and 1921.

In

1934, there was one hospital bed for 3800 people in

British India

and this figure included hospital beds reserved for the British rulers. (In

that same year, in the

Soviet Union

, there were ten times as many.) Infant mortality in

Bombay

was 255 per thousand in 1928. (In the same year, it was less than half that in

Moscow

.)

William

Digby (1849 - 1904)

noted in "Prosperous

British India"

in 1901 that "stated

roughly, famines and scarcities have been four times as numerous, during the

last thirty years of the 19th century as they were one hundred years ago, and

four times as widespread."

In Late

Victorian Holocausts,

Mike

Davis

points out that here were 31(thirty one) serious famines in 120 years of British

rule compared to 17(seventeen) in the 2000 years before British rule.

Land

that once produced grain for local consumption was now taken over by by former

slave-owners from

N. America

who were permitted to set up plantations for the cultivation of lucrative cash

crops exclusively for export. Particularly galling is how the British colonial

rulers continued to export foodgrains from

India

to

Britain

even during famine years.

Annual

British Government reports repeatedly published data that showed 70-80% of

Indians were living on the margin of subsistence. That two-thirds were

undernourished, and in

Bengal

, nearly four-fifths were undernourished.

Contrast

this data with the following accounts of Indian life prior to colonization:-

"

....even in the smallest villages rice, flour, butter, milk, beans and other

vegetables, sugar and sweetmeats can be procured in abundance .... Tavernier

writing in the 17th century in his "Travels in India".

Niccolo

Manucci (1639

- 1714) the Venetian who became chief physician to Aurangzeb (also in the 17th century)

wrote:

"Bengal is of all the kingdoms of the Moghul, best known in

France

..... We may venture to say it is not inferior in anything to

Egypt

- and that it even exceeds that kingdom in its products of silks, cottons,

sugar, and indigo. All things are in great plenty here, fruits, pulse, grain,

muslins, cloths of gold and silk..."

The

French traveller, Francois Bernier (1625

- 1688) also

described 17th century Bengal in a similiar vein:

"The knowledge I have

acquired of Bengal in two visits inclines me to believe that it is richer than

Egypt

. It exports in abundance cottons and silks, rice, sugar and butter. It produces

amply for it's own consumption of wheat, vegetables, grains, fowls, ducks and

geese. It has immense herds of pigs and flocks of sheep and goats. Fish of every

kind it has in profusion. From Rajmahal to the sea is an endless number of

canals, cut in bygone ages from the

Ganges

by immense labour for navigation and irrigation."

The

poverty of British India stood in stark contrast to these eye witness reports

and has to be ascribed to the pitiful wages that working people in India

received in that period. A 1927-28 report noted that

"all but the most

highly skilled workmen in

India

receive wages which are barely sufficient to feed and clothe them. Everywhere

will be seen overcrowding, dirt and squalid misery..."

Ancient

Monuments

Perhaps

the least known aspect of the colonial legacy is the early British attitude

towards

India's historic monuments and the extend of vandalism that took place. Instead,

there is this pervasive myth of the Britisher as an unbiased "protector of

the nation's historic legacy".

Plans

to dismantle the Taj Mahal were in place, and wrecking machinery was moved into

the garden grounds. Just as the demolition work was to begin, news from

London

indicated that the first auction had not been a success, and that all further

sales were cancelled -- it would not be worth the money to tear down the Taj

Mahal. Thus the Taj Mahal was spared, and so too, was the reputation of the

British as

"Protectors of India's Historic Legacy"

! That innumerable

other monuments were destroyed, or left to rack and ruin is a story that has yet

to get beyond the specialists in the field.

India

and the Industrial

Revolution

Perhaps

the most important aspect of colonial rule was the transfer of wealth from

India

to

Britain

. In

his pioneering book, India

Today,

Rajni

Palme Dutt

conclusively demonstrates how vital this was to the Industrial Revolution in

Britain. Several patents that had remained unfunded suddenly found industrial sponsors

once the taxes from India

started rolling in. Without

capital from

India

, British banks would have found it impossible to fund the modernization of

Britain

that took place in the 18th and 19th centuries.

In addition, the

scientific basis of the industrial revolution was not a uniquely European

contribution.

Several civilizations had been adding to the world's scientific database -

especially the civilizations of

Asia, (including those of the Indian sub-continent). Without

that aggregate of scientific knowledge the scientists of

Britain

and

Europe

would have found it impossible to make the rapid strides they made during the

period of the Industrial revolution. Moreover,

several of these patents, particularly those concerned with the textile industry

relied on pre-industrial techniques perfected in the sub-continent. (In

fact, many of the earliest textile machines in

Britain

were unable to match the complexity and finesse of the spinning and weaving

machines of

Dacca

.).

Some

euro-centric authors have attempted to deny any such linkage. They have tried to

assert that not only was the Industrial Revolution a uniquely British/European

event - that colonization and the the phenomenal transfer of wealth that took

place was merely incidental to it's fruition. But the words of Lord

Curzon

still ring loud and clear. The Viceroy of British India in 1894 was quite

unequivocal, "

India

is the pivot of our Empire .... If the Empire loses any other part of its

Dominion we can survive, but if we lose

India

the sun of our Empire will have set."

Lord

Curzon knew fully well, the value and importance of the Indian colony. It was

the transfer of wealth through unprecedented levels of taxation on Indians of

virtually all classes that funded the great "Industrial Revolution"

and laid the ground for "modernization" in

Britain

. As early as 1812, an East India Company Report had stated "The

importance of that immense empire to this country is rather to be estimated by

the great annual addition it makes to the wealth and capital of the

Kingdom....."

(source: The

Colonial Legacy - Myths and Popular Beliefs - indiaresource.com).

It is painfully evident that the

West has approached Asia "armed with

gun-and-gospel truth," systematically imposing its religions,

its values, and its legal and political systems on Eastern nations, careless of

local sensitivities and indifferent to indigenous traditions."

(source: Oriental

Enlightenment: The encounter between Asian and Western thought - By J. J.

Clarke p.6-8).

The timeline of contact of both Islam and the British with the

Indian subcontinent is a chronicle of butchery, plundering of wealth and

resources, destruction of Hindu/Buddhist temples and property, slavery and

rounding up of women for harems, forced religious conversions and taxation, and

degradation of local customs and traditions that led to cultural, religious,

economic, political and social upheaval of unprecedented proportions that modern

India is only now coming to grips with. While

the Islamic bunch had the barbaric and destructive characteristic as their

hallmark, the British were a little more refined, emphasizing on economic

exploitation, but no less generous or kind towards their subjects.

(source:

Resurrecting

India's True History - By Hari Chandra -sulekha.com).

***

Smelling British Sahibs learnt to bathe in India - Civilizing the British?

The

first Englishmen who came to India as servants of the East India Company were

bewildered by many of our customs. Many of them commented on, in their letters

home, the habit, among certain classes of the Hindus, of taking a daily bath.

The

early factory-hands of John Company in India may have been somewhat scandalized

by the fact that Hindu men and women of good families should not mind taking

their baths in full view of others, what they found even more strange

was that they should be washing their bodies at all. The

early factory-hands of John Company in India may have been somewhat scandalized

by the fact that Hindu men and women of good families should not mind taking

their baths in full view of others, what they found even more strange

was that they should be washing their bodies at all.

For

the British, the process of washing the

body entailed lying prone in a tub half full of hot water. And how many houses

in pre-Industrial England could have had metal containers large enough to

accommodate grown men and women, and, even more, the facilities to heat up

enough water? The

conclusion was inescapable. For most Englishmen of the 17th and 18th centuries,

a bath must have been a rare experience indeed, affordable to the very rich, who

perhaps took baths when they felt particularly obnoxious, what with their zest

for vigorous exercise, such as workouts in the boxing ring or rowing or riding

at the gallop over the countryside. What a sensual pleasure it must have been to

lie soaking in a tub full of scalding hot water? But such indulgences were